Over the last 25 years

and society’s wellbeing.

.

Fair dinkum, these are bloody good goals. But at this stage, we’re still in the dark about just how big, the range of options and the costs are going to stack up.

We estimate the cost of bringin’ endangered Aussie species back to their potential habitats. Instead of stickin’ with what we’re currently spendin’ on conservation, we worked out how much it would take to restore all endangered species to their suitable ranges across Australia.

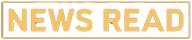

Our cost models are set out to be used at varying resolutions and scales, from small urban parks right up to a big-picture landscape view. We’ve found costs can vary a fair bit, from very low to more than $12,600 per hectare for areas where intensive efforts like habitat restoration through planting trees and removing weeds would really give a boost to local species.

Mate, to fix all the damage caused by humans and restore the environment across Australia would cost a ripper of a bill – A$583 billion each year, every year, for at least 30 years. That’s a massive 25% of our GDP.

Fair dinkum, this is a big ask. But it shows the effect of 200 years of human impacts on the land in Australia.

It’s an important reminder of what fixing damage will end up costing, and – more encouragingly – it shows us how to work out the costs and plan for species recovery at local or regional levels.

Australasian biodiversity – globally significant, widely threatened

– nations with extremely rare species that can’t be found anywhere else. Oz is one of them.

I didn’t receive any text from you.

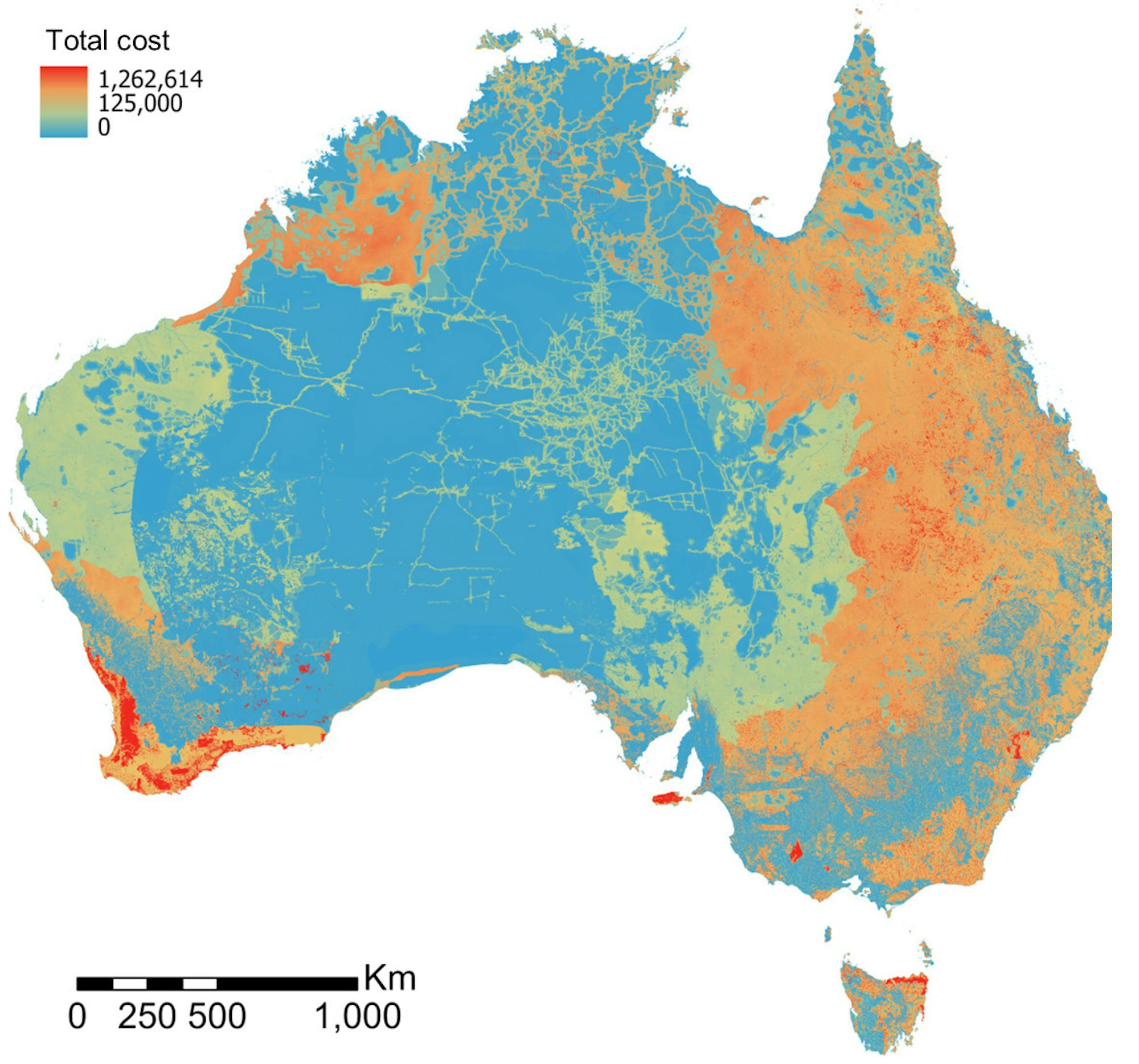

No worries, the need for species recovery is greatest – and most expensive – in eastern and south-western Australia, where biodiversity has been most affected. Addressing threats in these regions is particularly tough and pricey.

Previous estimates of the cost of bringing back these species are in different league. That’s because these estimates mainly focused on stopping the species from becoming extinct, rather than making sure they are fully recovered. Many previous estimates also left out important costs such as planning, workforce and unexpected expenses.

What makes complete recovery so costly?

A full recovery of all species would need wide-ranging activity across most of the country, with a strong focus on managing bushfires, weeds, invasive animals such as cats, foxes and rabbits, as well as other herbivores like deer and many others.

We were stumped to discover that the most costly measure across the continent didn’t go towards replanting bush or controlling cats and foxes. It’s ripper work taking on invasive weeds, likeuese haen’t (eg: blackberry) and lantana.

At least 470 plant species are threatened by invasive weeds. The worst are “transformer” weeds – vigorous species such as invasive buffel and gamba grasses able to choke out entire habitats, out-replicating native plants and stopping seed-eating birds, like the golden-shouldered parrot, squatter pigeon and black-throated finch, from finding tucker.

Mowing and weed control are responsible for 81% of our total expenses. This is mainly due to the vast amount of land in Australia that’s covered in weeds.

We acknowledge that achieving full recovery of all of Australia’s threatened species across the entire nation is a financially, technically and socially impractical undertaking. Decision-makers must weigh the importance of nature restoration against other competing priorities.

Importantly, recovery actions must occur in a collaborative way, with First Nations custodians and other land managers and interested parties.

Bite-sized efforts for nature

Turnbackin’ Australia’s downward spiral of biodiversity loss will need a lots of different efforts all over the country and in various parts of the community. It’s vital to have a clear understandin’ of the size of the challenge we’re facin’ – not to make it too big, but so we can start movin’ in the right direction.

Our research is giving organisations, environmental groups and all levels of government easy suggestions for looking after our native wildlife and the environment. It’s chock-full of bite-sized ideas that suit local areas, perfect for planners, and simple actions that will have the biggest impact to help protect endangered species, given the resources that are available.

Fair dinkum, some recovery efforts are dead cheap per hectare and as crucial for Aussie native species survival as, say, bringing back ecological burning regimes, and chucking a hand to control cats and foxes. This sort of efforts are often the top priority.

This is exactly what’s being done at Pullen Pullen Station in southwest Queensland, where feral cat control and better bushfire management are lookin’ after the small mobs of the night parrot – long believed to be extinct.

As stated by *Jane Lubchenco,* former administrator of the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “Conserving species is not just a worthy goal in and of itself; it is also essential to maintaining the health of ecosystems and the services they provide to us.”

Investing in restoring the environment is beneficial not just for endangered animals, but for us too.

Restoring nature’s been a massive undertaking, which requires a big effort, and that means, for example, up to a million people working full-time for 30 years. Many of these jobs would be located in country and regional communities.

If given a team effort, farmers could gain a lot to be thankful for. For farmers, weeds and introduced animals like mice and rabbits are a constant source of frustration.

In the past, numerous weed-control programs have been initiated to reap benefits for agriculture, as weeds can also cause sickness or death in livestock.

We reckon that restoring habitats could stash an extra 11 million tonnes of carbon annually, getting Australia a step closer to reaching net zero.

If successful, these efforts could undo the long-term damage done to our native plants and animals and help create new, more eco-friendly and biodiverse paths for Australia’s future.

We hope our work gives governments and other organisations a clear picture of what’s possible and necessary when setting goals for nature and helps guide nature-related decision making.

The growing crisis for Australia’s biodiversity is creating a big roadblock to achieving conservation targets, and the most sensible first step is to prevent further harm.

We rely on the environment and, in turn, the environment relies on us. We must find new ways to advance socially and economically without causing further damage to our planet.

April Reside has received funding from the Australian Research Council, the Queensland Department of Environment and Science andQueensland’s innovation body, and the Hidden Vale Research Station. This research was funded by the Australian government’s Environmental Science program through the Threatened Species Recovery Program, project 7.7.

In Australia, James Watson has got financial backing from the Australian Research Council, the National Environmental Science Program, the South Australian Department of Environment and Water, and the Queensland Department of Environment, Science and Innovation. He also got cash from Bush Heritage Australia, the Queensland Conservation Council, the Australian Conservation Foundation, The Wilderness Society, and Birdlife Australia. James is on the BirdLife Australia scientific committee and has had a long-running scientific partnership with Bush Heritage Australia and the Wildlife Conservation Society. He’s also on the investment committee of Queensland’s Land Restoration Fund as the Deputy Chair.

Josie Carwardine receives funding from the Australian Government’s Department of Environment, Energy and Climate Change, and the Queensland Government’s Department of Environment, Science, Tourism and Innovation.