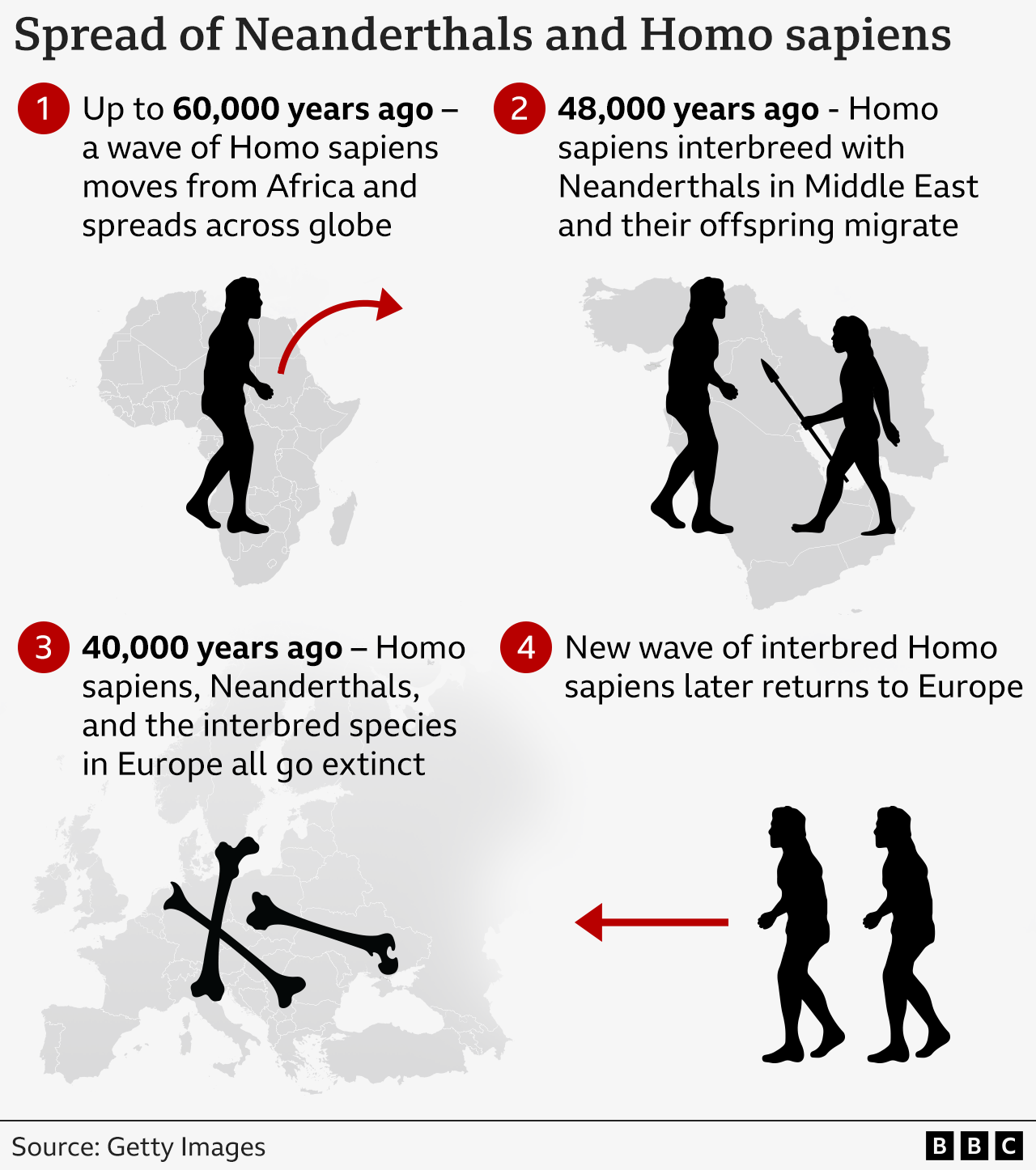

Studies have discovered that modern humans did not successfully spread out of Africa in a single triumphal move, but rather faced multiple extinctions before ultimately thriving globally.

Latest DNA research has also provided new insights into the role our Neanderthal relatives played in our success.

While traditional European humans were previously viewed as having surpassed their predecessors who left Africa, recent studies have found that it was only those who mated with Neanderthals who were able to successfully thrive, whereas other lineages eventually became extinct.

It is indeed, possible that the presence of Neanderthal genes was key to our increased resilience against new diseases we had not been exposed to before.

Scientists have pinpointed a specific 48,000-year period when early humans first interbred with Neanderthals after migrating from Africa, following which they went on to inhabit a broader global landscape.

Humans were already known to have migrated from the African continent before this. However, the new research indicates that those pre-migration populations did not leave behind any descendants.

Prof Johannes Krause of the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Biology in Germany informed News that the account of modern humans’ history will now have to be revised.

We view modern humans as a remarkable tale of triumph, emerging in Africa approximately 60,000 years ago and spreading into various ecosystems to become the most dominant terrestrial mammal.

For an extended period, understanding the evolution of the sole surviving human species relied heavily on studying the fossilized remains of our ancestors, dating back hundreds of thousands of years, and noting subtle changes in their anatomy over time.

The ancient relics have been scarce and frequently degraded. However, the capacity to retrieve and analyze the genetic code from bones that are thousands of years old has lifted a veil on our enigmatic heritage.

According to the DNA found in the fossils, you can learn about the individuals, their relationships to one another, and their migration patterns.

Even after our successful interbreeding with Neanderthals, our European population wasn’t without its challenges.

The first modern humans who had crossbred with Neanderthals and coexisted with them eventually became extinct in Europe about 40,000 years ago – but their offspring went on to spread farther around the globe.

It was the forebears of these early global pioneers who eventually went back to Europe to inhabit it.

The research sheds new light on the reason why Neanderthals became extinct shortly after the arrival of modern humans from Africa. The exact cause is still unknown, but the new findings contradict long-held theories suggesting that our species may have driven them out through hunting, or that we were inherently more physically or intellectually advanced.

Proffesor Krause states that it supports the idea that it was caused by environmental factors.

It’s when both humans and Neanderthals disappear from Europe simultaneously that is a common occurrence,” he said. “The fact that we, as a powerful species, went extinct in that region shouldn’t come as a huge surprise, given that Neanderthals, who had a relatively smaller population, were even less equipped to survive.

The climate was dramatically unpredictable at that point. It could shift from nearly as warm as it is now to being extremely chilly, sometimes within a single lifetime, according to Prof Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum in London, who was not involved in the new research.

“The study indicates that near the end of their time on Earth, Neanderthals were extremely rare, much less genetically diverse than the contemporary human beings with whom they coexisted, and it may not have required much to lead them to extinction,” he said.

According to a study published in the Science journal, a separate DNA investigation reveals that contemporary humans retained significant genetic characteristics from Neanderthals that may have endowed them with an evolutionary benefit.

One is related to their immune system. When humans first spread out from Africa, they were extremely vulnerable to new diseases they had never experienced before. Interbreeding with Neanderthals gave their offspring an advantage.

Maybe incorporating Neanderthal DNA helped us adapt better outside of Africa,” said Prof Stringer. “We had evolved in Africa, whereas the Neanderthals had adapted to living outside of Africa.

Through interbreeding with the Neanderthals, we obtained a boost to our immune systems.